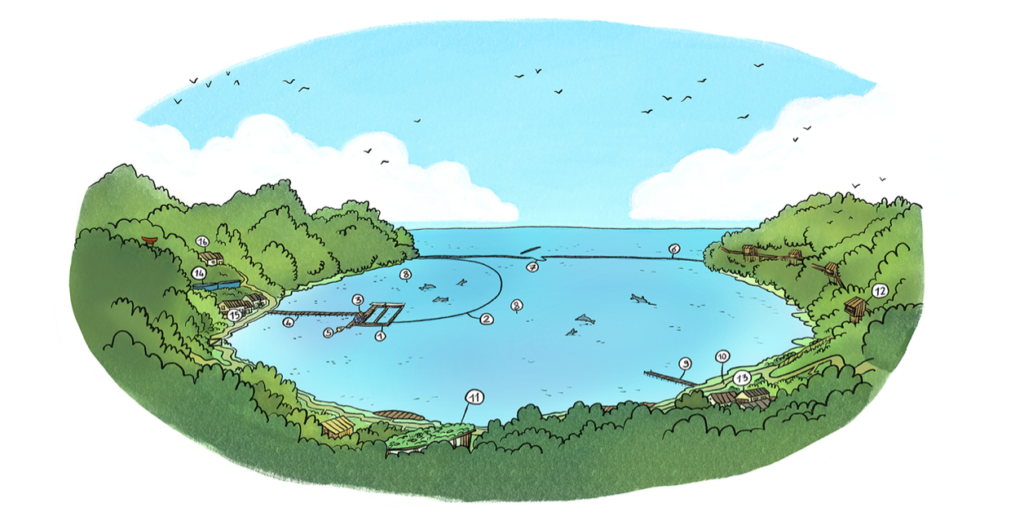

Written by Leina Sato, Director of Project Anima which utilizes music, art, and ritual to engage and build connections with Japanese citizens, authorities, and policymakers. Project Anima holds an annual ceremony in Taiji to honor the cetaceans who lost their lives in the town’s infamous drive fishery featured in our film The Cove.

In the spring of 2022, after our first ceremony at the Cove – I still remember the otherworldly light of that morning, the sun rising in perfect alignment with the mouth of bay, setting the world ablaze in orange and golden hues- I interviewed Ema. Ema is a Japanese singer (and shaman, although she’d never proclaim herself as such). One of the first artists that accompanied us to Taiji, she performed a beautiful ritual in homage to the cetaceans who had lost their lives that year.

“There is so much that we are not aware of” she said, talking about Japan. “So much, also, that we pretend not to see.”

“There is this wound that the Japanese people bear from time immemorial; and this has prevented us to face certain things. But becoming aware of what is happening in Taiji is for us an opportunity to rekindle the connection we lost with the dolphins and the whales.”

What is the wound she was alluding to? I could only assume, knowing her, that she was referring to the wound of separation. Japan’s departure from an animist worldview, a way of relating to the world that predated the Jomon era. The stuff of lore, myths and magic when humans considered Nature as kin, and animals and men shared a common tongue.

Standing at the Cove for the third time this year, I felt nostalgia flaring up. Perhaps it was not so much nostalgia as it was a sense of longing, for what had been lost, and what had been forgotten. I felt how deep the wound was – but paradoxically enough, because it was so deep and the grief somewhat incommensurable, the potential for reparation and hope felt equally as great.

After the ceremony, the artists and I visited a dolphin swim facility right next to the Cove. Just as the year before, we had been granted permission to come and perform music for the captive dolphins. An imperfect- and perhaps somewhat derisory- attempt to communicate the complexity of our feelings, the grief and the love, through the universality of music and frequency. To say: “We see you. You are not forgotten.”

The concrete tanks here are unimaginably small. From the rooftop, where the facility is set up, the eye can’t help but travel back and forth from there to the Ocean, only a few steps away.

The physical proximity with the dolphins is unsettling. They are literally right there. No fence separating us. One can walk straight up to the edge of the concrete pool.

I go to one isolated dolphin, nearly falling onto my knees. I find him in the same exact position as when I’d left him, one year ago. His head resting on the edge of the pool, motionless. Staring right at me or perhaps, more accurately, staring right past me. As I look into his eyes, there seems to be nobody home. The physical body is here, a shell; his mind is clearly traveling elsewhere, it has vacated the premises out of his concrete isolation.

I inquire about him. “How long has he been here…?”

“Over twenty years,” I am told. He is an older male; he is not allowed, most of the time, to mingle with the rest of the females. His isolation is to prevent chaos and lust-driven frenzy. What else can one expect? His sole purpose here is to inseminate the females.

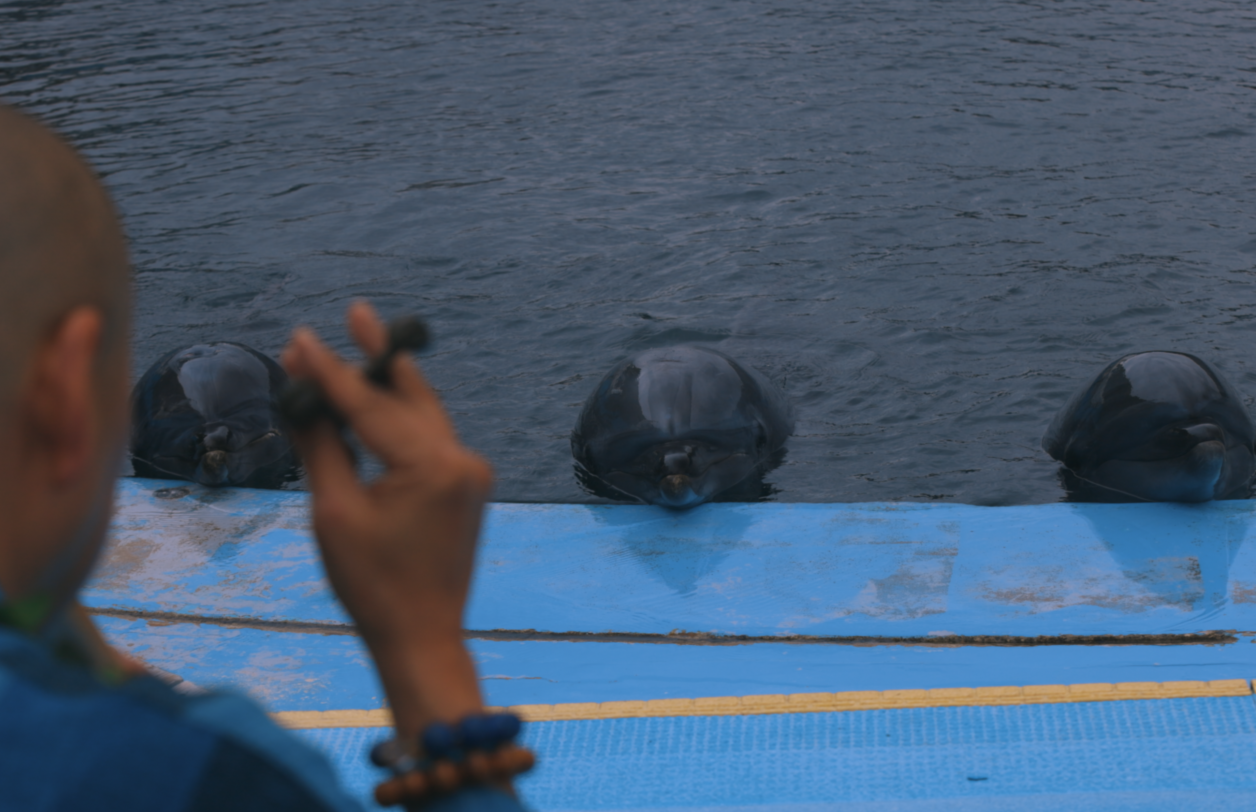

The music starts. The lone male turns his head in its direction. On the other side of the fence, the female dolphins are alert, giving their full attention to the musicians. It is an improbable sight, the four of them standing nearly upright in a neat row, like attentive spectators at a concert.

A few feet away, in a slightly larger tank, another scene is unfolding. Some dolphins have grabbed hold of yellow balls and are motioning to my friend to come and play. They keep tossing the balls at her, engaging her over and over again. My friend is squealing in delight.

For a brief moment, I feel consumed by outrage. Not directed at my friend but the situation itself, how grotesque it all seems. A voice rings in my head, imbued with self-righteousness: “Dolphins, I cannot possibly engage with you; that would be condoning what is happening here!” But then, my glance falls back on my friend, her voice chortling with laughter. I cannot help but see how candid they are, the dolphins and her. How pure their mutual desire for connection, to be simply and fully present with one another. I look at the musicians, their eyes half-closed in concentration, how involved they are in the expression of this moment they are creating for the dolphins. And then I look at the dolphins, their immense resilience.

I don’t fight back the tears. My heart feels on the brink of explosion.

Joanna Macy, the great environmental activist and scholar of Buddhism famously said: “The heart that breaks open can contain the whole universe.” It is my favorite quote of hers, along with her invitation to have the courage to sit with it all, “the beauty and the terror”, in reference to a poem of Rainer Maria Rilke.

“(…) You, sent out beyond your recall, Go to the limits of your longing. (…)Let everything happen to you:Beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final. (…)”

For me, Taiji is that kind of place. A liminal border, it undoes and transforms me. Every year, it grows on me, taking me farther towards the limits of my longing. It is what brings me back here, not so much the pursuit of justice but rather the longing, the hope of reparation.

Kneeling once more in front of the lone male, I recall the words of one of the musicians after our first visit here: “What touched me most is that despite the unimaginable trauma they must have gone through, the dolphins seem to try and stay true to who they are, in all circumstances. It made me want to work towards that, to become that kind of human, too.”

And so I whisper to this dolphin: “I don’t know if I can get you out of here but I promise you; I promise you I will do all that I can to bring this sanctuary project into being.”

It’s a vow destined partly to him, partly to myself. And as I keep looking into his eyes – this half-gone gaze which contains so much, grief, resignation, wisdom, solitude, I hear, as spoken back to me, the lines of Rilke’s poem. “Just keep going. No feeling is final.”

In addition to the ceremonies, Project Anima also aims to create the first rehabilitation/release/retirement center in Japan for cetaceans previously held in captivity. Learn more and support their mission here.